Finding Chata

Finding Chata: A new foundation created to find missing hikers solves its first case.

Written by FOF member Andrea “Andy” Lankford

Rosario “Chata” Garcia was a warm, friendly person but, during the summer of 2020, her family had noticed a change. The loving grandmother was now forgetting things that happened only five minutes earlier. One weekend, while visiting out-of-town family, Chata left her hotel room and couldn’t find her way back. “She was in the parking lot,” her daughter, Maggie Garcia Zavala, said in a story published by the Desert Sun. “She didn’t know what she was doing there … and she was crying.”

Like many of us, the seventy-three-year-old from Hemet, California was feeling cooped up and isolated during the pandemic. Rosario Garcia was married for over 51 years to a Vietnam veteran. She loved to dance and made friends easily everywhere she went. A few days after the incident at the hotel, on July 7, 2020, Chata left home in her silver 2016 Nissan Sentra to visit a friend. When she didn’t return home that night, her family reported her missing.

Two days later, a hiker found Garcia’s silver Sentra high centered on a rock on a rugged dirt road near the Sawmill Trailhead in Ribbonwood, forty-one miles from her home. The car keys and Chata’s purse were gone. County authorities searched for several days using ATVs, aircraft, and bloodhounds but they couldn’t find Chata.

Garcia’s friends and family searched for her as well. They posted flyers and pleaded for help on Facebook. “I just want answers. I just want to make sure that she’s OK,” Garcia’s daughter told reporter Sherry Barkas.

Rosario “Chata” Garcia

She was a loving grandmother, said to be the life of the party, and loved to dance.

Thousands of miles away, in Pennsylvania, Cathy Tarr (57) was having a bad summer. On August 23, two weeks before a surgeon would remove several cancerous tumors from Cathy’s breast, something even more horrible happened. Her sister, her niece, and a family friend were stabbed, beaten, and bitten by the niece’s an ex-boyfriend–a mentally unstable man who violated a restraining order and broke into their home carrying a dagger and a baseball bat.

Miraculously, they all survived the brutal assault. But Cathy’s younger sister had been stabbed in the throat and needed multiple surgeries to repair the damage. The task of cleaning up the crime scene fell upon Cathy. “It was a horrific attack, as you can tell from looking at all of this,” she told a reporter as they walked through her sister’s blood-spattered apartment, “I want you to see this because it shouldn’t have happened.”

Before and after her own surgery, Cathy searched for a new, safe place for her family to live. On top of this, there was the pandemic. One day, the stress of it all became too much. Cathy lost it, briefly, when she noticed her closet was full of coat hangers that weren’t all the same color. Inexplicably, this caused her to break down and cry.

Cathy Tarr on the trail during happier times.

Normally optimistic, Cathy tends to bulldoze her way through setbacks. The retired manager for Walgreens had spent the better part of the last three years searching for two hikers still missing from the Pacific Crest Trail—Kris Fowler and David O’Sullivan. Undeterred by her failure to find them, Cathy created a nonprofit in honor of Kris and David. Cathy wanted the Fowler-O’Sullivan Foundation (FOF) to help families of missing hikers, and her ambitions for how she could do that were limitless. But, after the assault on her family and the cancer diagnosis, Cathy had to set this dream aside.

I’m writing a book featuring Cathy’s search for Fowler and O’Sullivan. In October 2020, I met with her in Idyllwild, California to discuss how her work was going and the future of the foundation. I worried about Cathy. She was still sore from her surgery and exhausted by all that had happened. I feared that without Cathy’s energy and leadership our newly formed foundation might collapse.

The next morning, Cathy showed me a story she had read in the local newspaper. In 2020, four people went missing near Idyllwild, a small mountain village in Southern California. The local authorities had not been able to find them. To take Cathy’s mind off all her troubles back in Pennsylvania, I suggested we scout the last known points of two of those cases, to see if there was any way we could help. One of the sites we chose to visit was the Sawmill Trailhead, where Rosario Garcia’s car was found.

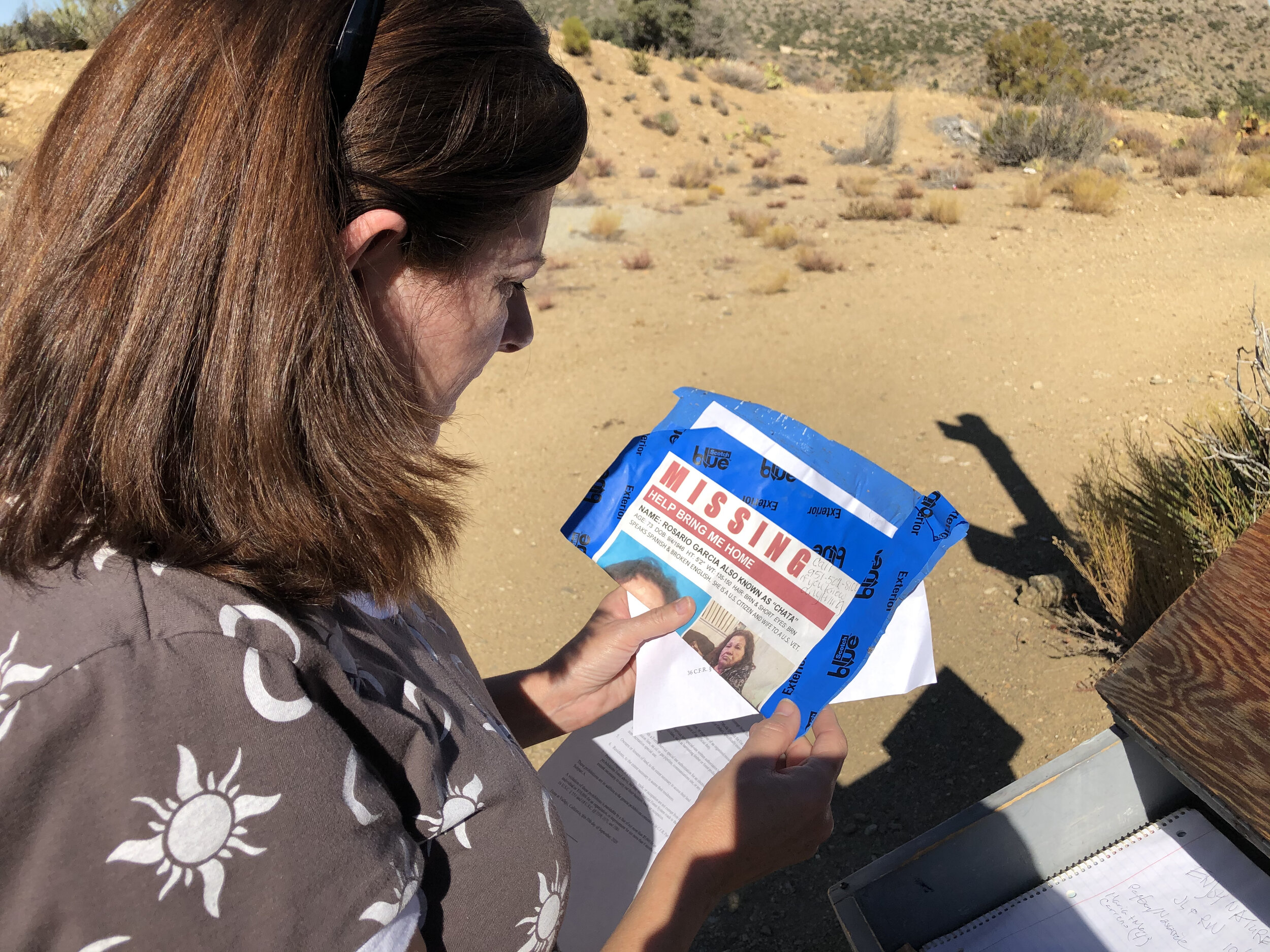

Cathy Tarr reviews the missing poster near the Sawmill Trailhead not far from where Rosario Garcia’s car was found by authorities.

Cathy and I walked from the parking lot up a dirt road to the Sawmill Trailhead. In the trail register, we found a missing person flyer and a note written by members of Garcia’s family. The desert terrain was mostly boulders, cactus, and brush. There were no tall trees and we saw large patches of open ground. Past experience told us this was a good environment to conduct a grid search by drone. Garcia was elderly and walked with a cane. She went missing in July. The daytime temperatures would have been extreme. She’s here, we both thought as we walked back to our cars, we can find her.

She’s here. We can find her.

As I had hoped, our scouting expedition reenergized Cathy. A month later, she returned to the site with Pam Coronado, another board member of FOF. Pam scratched up her new SUV while driving up the rugged road. When they reached the point where Garcia’s car was found high-centered on a rock. Cathy pinned the coordinates on the Gaia app on her phone. The women searched for a while on foot, battling cactus the entire time. When they decided to leave, Pam felt sad to think of someone’s mother lost out there all alone.

The desert near the Sawmill Trailhead is lonely and beautiful.

In 1999, Professor Pauline Boss pioneered the term ambiguous loss to describe the “frozen grief” suffered by “not knowing if a loved one is absent or present, dead or alive.” This type of grief is the hardest to bear. Loved ones of missing people suffer from ambiguous loss. So do the families of people with dementia.

“Her family probably believes no one cares,” Cathy said later. “I really want to help them.” But search efforts conducted by well-intentioned amateurs can raise a family’s expectations too high. Then, when the missing person isn’t found, all their hopes are dashed upon the rocks. Considering how our efforts might negatively impact Garcia’s family, Cathy decided FOF’s first search would be conducted quietly. That way, if her team failed, no one would be hurt.

“Her family probably believes no one cares. I really want to help them.” Cathy Tarr

When planning an aerial search for human remains, you can’t just call up any guy with a drone. Cathy had learned this the hard way during her years looking for O’Sullivan, who went missing in the San Jacinto Mountains north of Idyllwild in 2017. A successful drone search requires skilled operators who know how to capture high resolution images while flying precise grids. You also need a patient and persistent team of image scanners who are willing to spend their free time searching thousands of photographs for clues. Fortunately, Cathy knew the right people with the right skills for the job. She scheduled the search for a weekend in January 2021.

A professional and compassionate team.

Thursday, four drone pilots with Western States Aerial Search (WSAS) drove eleven hours from their home state of Utah to Southern California. Their leader, Greg Nuckols, had recently obtained nonprofit status for WSAS. Cathy had worked with Greg before. Over the years she had watched his team perfect their technique. In the last twelve months, WSAS pilots had obtained images that led to the resolution of two missing hiker cases.

Like Cathy’s nonprofit, WSAS never charges families of the missing for anything. And they do not accept rewards. Cathy booked the drone pilots an Airbnb and paid for their travel expenses using funds donated to the Fowler-O’Sullivan Foundation. Theresa Sturkie, the wife of a missing man Cathy helped find in 2019, cooked meals.

During the day, the pilots flew their drones over the area surrounding the road where Garcia’s car was found. At night, they downloaded thousands of high-quality images into their laptops. One pilot had to be at work Monday morning. The drone team drove all night Sunday and didn’t get home until very late.

Once the photographs were uploaded, it was time for the image scanners to do their work. On Sunday evening, Cathy sent her team a link to the high resolution image files.

One search image out of thousands taken of a search area in a heavily forested environment.

Morgan Clements CEO of GlobalIncidentMap.com was up late. Right away, he began a cursory search of the thumbnails to see which photos spoke to him. It was the first step in a tedious process Morgan had done before. In 2018 and 2019, he searched over 3,000 aerial images looking for O’Sullivan. In 2019, he squinted at hundreds of images before he found the bones of Paul Miller, a hiker who went missing in Joshua Tree.

At the start of his search for Rosario, Morgan took a moment to ask Mrs. Garcia to guide him to the right image.

At the start of his search for Rosario, Morgan took a moment to ask Mrs. Garcia to guide him to the right image. The quality of the WSAS photographs were impressive. Morgan could pick out items as small as a rusted tin can and individual blades of agave. He had already scanned over a hundred images when he spotted some clothing. He shared this photo with the FOF image search team under the caption “possible blue clothing, next to striped purse, on sloped ground.” In Missouri, where Morgan lived, it was nearly midnight.

The next morning, Cathy woke up early. As soon as she saw the photo Morgan posted, she texted me, “Almost positive we found Garcia.” Then she called Greg. Using the coordinates from the image with the clothing, Greg found more photographs from the same area. These images, taken from a different angle, left no doubt. Working together, WSAS and FOF had found human remains within 500 feet of where Garcia’s car was discovered.

Cathy reported this to the authorities. A few hours later, she led a convoy of law enforcement officers to the site. It had snowed the night before and the dirt road was wet. The deputy driving the front car got stuck in the mud. Cathy encouraged him to keep going. But more bad weather was on the way and snow covered the ground. The site was too difficult to reach in these conditions.

When the weather cleared, Riverside County was able to retrieve the remains and the coroner soon confirmed they belonged to Rosario Garcia. They saw no evidence of foul play. In one news report on the case, Riverside County sheriff’s Sgt. James Burton told reporters “trekkers” had spotted the remains.

In reality, the FOF search for Rosario Garcia was a professionally organized mission involving a dozen experienced volunteers, specialized equipment worth thousands of dollars, and hundreds of hours of time. “We are constantly training and improving our technique,” Greg Nuckols says of WSAS. “We’re passionate about the work. Our goal is to get the absolute best images possible so that folks like Morgan will be able to identify what they are seeing.”

Cathy believes FOF’s collaboration with WSAS is a “repeatable process” that can help find other missing people. “When official SAR groups lack the means or the funding for a well-coordinated drone mission with reliable image searchers,” Cathy says, “we can help.”

“When official SAR groups lack the means or the funding for a well-coordinated drone mission with reliable image searchers, we can help.” Cathy Tarr

For seven months Rosario Garcia’s family agonized over the fate of their loved one. Receiving news that a loved one’s body has been found is never a good thing. However, if Cathy Tarr hadn’t decided to take the case, Chata’s family would still be wondering what happened to her. “I call [Cathy] our Angel because she and her crew did something no one else could do,” Laura Atencio, Chata’s daughter-in-law, posted on Facebook. “That was to find her and bring her home to us.”

In addition to the names below we are grateful to all who made this search possible by donating their funds, time, and/or expertise to FOF and WSAS.

Fowler-O’Sullivan Foundation

Cathy Tarr, Morgan Clements, Pam Coronado, Andrea Lankford, Theresa Sturkie, Mackenzie Pollard.

Western States Aerial Search

Greg Nuckols, James Badham, Justin Holm, Brad Larson.